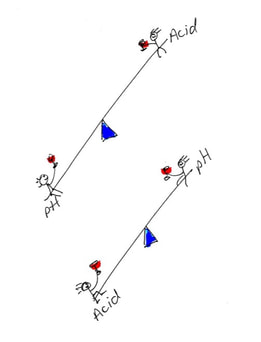

The more you salivate, the higher the acid level of the wine. The more you salivate, the higher the acid level of the wine. If you are handed a plate of sea bass that was pulled off the grill on a summer day, do you grace it with a splash or two of lemon juice? Refreshing, crisp acidity is a burst of excitement in your food and wine. Without acidity, wine would taste flabby and lifeless, as might that lovely sea bass. Acid contributes the tart, zippy, and/or sour flavors you experience in wine. The level can range from low to high, depending on the grape variety, growing conditions, climate, winemaking, and a host of other factors. Acid also performs a useful function: it inhibits the growth of bacteria and unsavory microbes. In other words, it acts as a preservative. If you enjoy the classic Italian dish, beef carpaccio, you understand the role of lemon juice or balsamic vinaigrette, aka acids, to protect the raw steak from bacteria and brighten up the flavor. Low-acid wines taste fuller in the mouth, giving you a soft, round, mellow experience. Wines with high acidity deliver a leaner, more bracing adventure, like taking a vigorous run in cool weather. Wines with high acidity can help improve the wine as it ages, while those with low acidity can cause the wine to lose vibrancy. That is why collectors look for medium to high acidity in the wines they plan to age (along with substantial tannins, alcohol, fruit concentration, and possibly sweetness). A low-acid wine has less protection from contamination so it is customarily drunk young. Sometimes low acid wines, with their sensitivity to oxidation, develop a hazy appearance, though this can be avoided by the winemaker with the addition of sulfur dioxide and/or filtering. Don’t restrict yourself to either low-acid or high-acid grape varieties; try them all. Many times I have made the mistake of thinking a wine did not have the right resumé only to be surprised and thrilled by the wine’s magnificence. In fact, I made the same mistake when a man who was a few years younger than me (wrong resumé) working at the same firm (double wrong resumé) dropped by my office to “chat” some years ago. That man later turned out to be my husband, Peter.  Wines with a low pH have high acidity while wines with a high pH have low acidity. Wines with a low pH have high acidity while wines with a high pH have low acidity. I am also guilty, in the past, of being reluctant to try a bottle of wine made from a low-acid grape varietal. I am a fan of medium- to high-acid wines, so how could wine made from a low-acid grape be a thrill? Once again, what actually happened differed from what I had expected. I often drink a Fino or Manzanilla Sherry as I prepare dinner. These are among the driest, least acidic wines in the world and they are made from the Palomino Fino grape. Sherry is an acquired taste, and over time, my love affair with Sherry has waxed to the point of full-on passion. (Peter knows this and is fine with it.) My experience with Sherry has turned me into an enthusiastic believer in wines made from low-acid grapes. Conversely, I have been sorely disappointed by wines with a resumé that should have led to an absolute knockout experience. Like some men I dated before meeting Peter. Some truly delicious wines, such as Sémillon, Grenache and Ruchè, are low-acid varieties. When working with low-acid grapes, the vintner can use varying techniques, such as picking the grapes early before the acidity drops too low or blending with high-acid grapes, to keep the wine fresh and satisfying. An example of this type of blending: the great white Bordeaux whites, where the high-acid Sauvignon Blanc is blended with the low-acid Sémillon to create world-class wines of bright acidity and depth of flavor. The high-acid Carignan grape is a perfect blending partner to Grenache which is a low-acid grape. We have a lot of preconceived notions about the wines we will or will not drink, and that’s why it is important to keep an open mind. This week I was in the mood to drink something Spanish, so I sampled a 2018 bottle of Rueda over the course of five days. (Yes, it was one bottle revisited in small amounts over the course of a workweek.) Rueda is Castilla y León’s oldest demarcated wine region, producing almost exclusively white wines composed of their star, the Verdejo grape, which is a crisp variety. Makers often include Sauvignon Blanc or Viura when it is a blend. This bottle’s list of attributes gave me no doubt that I would enjoy a rewarding experience. It was the flagship wine of the maker. The wine was produced from one-hundred percent Verdejo grown on “un-grafted, pre-Phylloxera vines that are over one-hundred years old.” The label waxed on about citrus flavors, a viscous mouthfeel and a mid-palate that is “full-bodied with racy acidity” as well as a “lingering finish.” I opened the bottle and found the wine to be a mere shadow of what I was expecting, not only due to the optimistic write-up but because I have enjoyed many remarkable Ruedas in the past. Right resumé, disappointing wine. Tartrate crystals or "wine diamonds" are not made of glass and do not affect the aroma, taste or quality of your wine. Rueda, incidentally, is Spain’s largest producer of white wine. There are many brisk and delicious bottles coming out of Rueda, with lemon, lime, peach and bayleaf characteristics at prices that don’t make you think twice. I was mollified to find that this particular wine woke up a bit in terms of flavor on the fifth day, and I was glad I had not added the bottle to my collection of cooking wines on the kitchen counter. When I move a bottle to the kitchen counter, it is the equivalent of subjecting the bottle to wearing a dunce cap while facing the wall. These are bottles that did not make the cut. A wine’s acidity starts in the vineyard and is affected by soil, climate, canopy management, and other factors. At the beginning of the growing cycle, unripe grapes are naturally acidic. This is mother nature’s way of making the berries unappealing to birds and mammals who may want to eat them. As the grapes ripen and their sugar content rises, their acidity level goes down. Mother nature is now ready to attract animals to the seeds; she counts on them to eat and then scatter the seeds for the proliferation of the species. Climate also influences the acidity of grapes. If you drink a wine with high acidity, it may have been grown in a cool climate or a region with cool nighttime temperatures. Grapes from cool climates tend to retain their acidity much better than those grown in warm climates. However, some grape varieties are naturally acidic no matter where they are planted, such as Chenin Blanc and Sauvignon Blanc. The strength or intensity of acidity in wine is measured on a pH scale. Wines with a low pH generally present with high acidity while wines with a high pH have low acidity. But you do not need a pH meter to determine if a wine has low, medium, or high acidity. Your mouth reacts instinctively to the acidity of a wine through salivation, which restores your natural acid balance. The more you salivate, the higher the acid level of the wine. This is your personal measure for what is known as total acidity or titratable acidity. When you initially sniff a wine, you may anticipate high acidity if you detect tart or under-ripe fruit. On the red wine side, you may be able to pick up some clues as to the level of acidity before taking a sip based on color. Red wines with high acidity tend to be a bright ruby color. Those that are on the low end of the acid scale can have a purple or blue hue. Low-acid wines may turn brownish because they are more sensitive to oxidation.  Refreshing, crisp acidity is a burst of excitement in your food and wine. Refreshing, crisp acidity is a burst of excitement in your food and wine. Producers of whites that are too acidic can use malolactic fermentation (MLF) to tone down the crispness. MLF converts harsh malic acid, the type you might recognize in green apples, to the more soft, silky lactic acids you get from the milk you drink. Almost all reds go through MLF, and this process helps stabilize the wines. You will not detect MLF’s dairy aromas in reds. Makers of whites can prevent or induce MLF, based on the style they wish to produce. In colder growing regions, winemakers count on MLF to help them soften the wines that are overly acidic due to under-ripening. In warm regions, winemakers fight low acidity caused by sunlight and warmth, so they might block MLF in an effort to retain as much acidity as possible. Some winemakers balance out high acidity in a wine by blending in a sweeter wine . Or, a high-acid wine’s fermentation can be halted to produce a sweet wine that will nicely balance the wine. This is an approach you will see in sweet German Rieslings, for example, no blending required. Foods that have sweetness, saltiness or fat often make good pairings with high-acid wines. On the other hand, if a wine’s level of acidity is low, the winemaker can add tartaric acid to the grape juice prior to or during fermentation. Tartaric acid is a natural component of grapes, so adding it to the grape must is generally accepted as one method of making up for low acidity. It is usually added in powdered form and derived from grapes. If tartaric acid is added after fermentation, it is usually to cover up a mistake made in the cellar. Tartaric is the most important type of acid found in wine, providing balance and aging potential. Sometimes tartaric acid, when chilled, forms a compound that is responsible for the small crystals that you may happen to notice when you open a bottle of wine. The crystals are known as tartrate crystals or "wine diamonds" and they are harmless. Tartrate crystals are not made of glass and do not affect the aroma, taste or quality of your wine, but they will never go away unless you filter them out with a muslin cloth or at least mitigate the situation by decanting your wine. Personally, I am not bothered by tartrate crystals but it is nice to understand what they are so you can set the record straight with friends who express concerns about them. Have fun comparing a crisp white to a low-acid white and do the same for reds. Or, conduct a blind tasting of crisp and low-acid wines with friends and offer prizes to those who can identify what differentiates the wines. Cheers! Crisp/Acidic Varieties Whites: Albana Albariño Aligoté Madeleine Angevine Assyrtiko Bourboulenc Carricante Chasselas Chenin Blanc Colombard Cortese Cserszegi Füszeres Dafni Dry Hungarian Furmint Falanghina Friulano Godello Graševina Greco Gros Manseng Grüner Veltliner La Crescent Loureiro Moschofilero Melon de Bourgogne (Muscadet) Petite Arvine Petit Manseng (Jurançon, Pacherenc) Picpoul de Pinet Prié Blanc Poulsard/Ploussard Riesling Robola Sauvignon Blanc Savagnin Silvaner/Sylvaner St. Laurent Timorasso Torrontés Trebbiano Spoletino Verdejo Verdicchio Vidal Xarel-lo Reds: Aglianico Baga Barbera Blaufränkisch/Lemberger Bobal/Bovale Bonarda/Douce Noir/Charbono Carignan/Cariñena/Mazuelo Chambourcin Corvina Counoise Freisa Frappato Fumin Gamay Graciano Lagrein Mondeuse Noire Nebbiolo Petite Sirah Plavina Refosco (Colli Orientali) Sangiovese Zweigelt Low Acid Varieties Whites: Bacchus Catarratto Coda di Volpe Gewürztraminer Marsanne Malvasia Bianca Müller-Thurgau Muscat Blanc/Moscato Palomino Fino/Listán Blanco Pinot Blanc Sémillon/Semillon Reds: Dolcetto Garnacha/Grenache Montepulciano Négrette Pinotage Ruchè Tempranillo This is one in a series of Grape Detective blogs featuring the attributes of wine and how your love for a specific wine grape may lead you to discover new grapes with similar characteristics. The focus of the list is grape variety and does not include blends, wine regions, or styles.

0 Comments

Bitterness plays a nice counterpart to balance out the aroma of flowers. Bitterness plays a nice counterpart to balance out the aroma of flowers. Once in awhile, you run across a white wine with a surprising mouthfeel or flavor, something that takes you aback and causes you to pay attention. Wines with phenolic bitterness may be among them. Certain grape varieties are known for producing wines that finish with a subtle and pleasant bitterness reminiscent of the sensation you get after eating a young almond or a grapefruit pith. This bitter aspect refreshes and dries out your mouth in preparation for the next drink. Phenolic bitterness causes polarities among drinkers as most people either love it or hate it. A difference of opinion over phenolic bitterness can occur between happily married couples who have developed a habit of sharing a bottle. Peter and I typically open a bottle with dinner, and the talk sometimes turns to a discussion of the wine that has been poured. I might ask, “What do you think of this Cabernet Franc?” To which he might respond, “Give me a minute,” and take an assessing drink. His answer: “There’s just not much there for me. It just doesn’t do it for me.” It’s a real head-scratcher when your partner does not share your zest for something you find completely scrumptious. For example, this very morning I got around to tasting a white plum that I had picked up at the farmers market on Sunday. It was so delicious that I felt I had to share it with Peter as part of our marital contract. I cut off a generous portion of the plum with my Japanese pairing knife and offered it to him as though I was the Eve to his Adam. Peter took a bite. To my surprise, his face took on a pained expression and he said, “It’s too sour!” To which I responded, “The tartness is the best part!” I understand intellectually that we are each entitled to our own opinion of what we like and don’t like, so I refrained from explaining that the tartness of the plum was balanced by the fruit’s sweetness and flavor elements. I took back from Peter what was left and consumed the balance of the plums, guilt-free.  Italians are known for enjoying food and beverages with pleasantly bitter flavors. Italians are known for enjoying food and beverages with pleasantly bitter flavors. Italians are known for enjoying food and beverages with pleasantly bitter flavors. Think about radicchio, Tuscan kale, dandelion greens, Amaro, Negroni, and Fernet Branca. Bitterness is also an essential element in Indian cuisine. Chefs build recipes with ingredients like bitter gourd, neem leaves, and fenugreek seeds and leaves, to mention a few. Meanwhile, food writers and scientists alert us that bitterness is becoming less prominent in American food and drink, leading to a loss of dietary diversity and complexity. The long and short of it is, if you enjoy food and beverages that offer the interest of savory or bitter characteristics rather than strictly fruity and sweet, wines with phenolic bitterness may be your cup of tea. Just maybe not your drinking partner’s. Right now as we speak, I am enjoying a 2019 Maidenstoen Grüner Veltliner from Edna Valley, located in San Luis Obispo County, California. Not only am I enjoying the pleasingly bitter finish but also the wine’s rich, generous body. Grüner can also be made in a leaner, crisper style, but this maker chose a more opulent approach. Pale lemon in color, it has a somewhat cloudy or hazy appearance, alerting me that this wine was possibly not fined or filtered. While I admire the glorious beauty of a crystal clear wine or beer, this dirtier style often includes more than the usual helping of flavor compounds that might otherwise have been stripped away. Fining and filtering involves removing fine particles before bottling; it also stabilizes the beverage. The Grüner in front of me has a medium-intensity nose of peaches, lemon drops, lilies, banana, lychee, butter, smoky yellow cheese, almonds, vanilla, white pepper, and a surprisingly fresh and wonderful hint of raw peas soaking in water. It is a dry wine, and I am guessing that the alcohol is higher than its Austrian counterparts because we are talking about grapes that were grown under the warm California sun. Grüner originated in Austria, probably in Niederösterreich (lower Austria), and it is the country’s signature white wine grape. Looking at the label of this California-grown and produced wine, we are at fourteen percent alcohol by volume. Edna Valley has one of the longest growing seasons in California. Warm weather and longer hang time allow the grape to fully ripen in the vineyard and gain in sugar content, driving up the alcohol level. If you love the tannins in red wine, you may be intrigued to explore white wines with this type of texture. The majority of Austria’s Grüners fall somewhere between eleven point five to thirteen percent ABV, largely due to the country’s cool continental climate. Grapes grown in cool climates tend to have lower alcohol levels and higher acidity than those grown in warm areas. However, you can expect a Grüner to have a high level of acidity regardless of where it is grown and the same is true with the Chenin Blanc grape. Some varietals retain their hallmark characteristics regardless of where they are grown. In our Edna Valley tasting, the flavors of this Grüner glide along on a carriage of high tangy acidity, and it is no surprise. The lavish body and gracefully lingering bitter resolution have me thirsting for the next sip. My assessment: I am going to quickly pause this conversation to re-order this wine for my next delivery. Okay . . . sadly this wine is sold out, according to the online merchant, so it looks like I am not the only one looking to repeat the experience. If you love the tannins in red wine, you may be intrigued to explore white wines with this type of texture. Wines with phenolic bitterness lend themselves to astringency on the palate, similar to a red wine of somewhat low to moderate tannins. Notice that several varieties on the list are aromatic wines with conspicuous floral qualities on the nose. The bitterness plays a nice counterpoint to balance out the aroma of flowers. Using any white grape variety, a winemaker can coax a sensation or a mouthfeel that differs from most other whites. In this case, the winemaker would have several techniques at her disposal. One approach involves keeping the juice in contact with the skins. Normally, the juice from white wine is separated from the skins and other matter upon arriving at the winery to keep the taste pure and to avoid oxidation. In some cases, however, the winemaker is looking to achieve pronounced flavor intensity and texture from the grapes. Skin contact facilitates the extraction of phenolic compounds into the juice. When the skins, seeds and other grape materials are not separated from the juice until after fermentation, the white wine is being vinified just like red wine. Such wines are commonly referred to as “orange wines” or “skin-contact” whites. Not all orange wines are the color orange, but they are certainly darker than traditional pale whites. The deeper color is leached from the grape skins, seeds and perhaps the stems. Oxidation also plays an important role in color, and the orange wine process invites oxygen to make an appearance during skin contact, thereby darkening the wine.  Bitterness is becoming less prominent in American food and drink, leading to a loss of dietary diversity and complexity. Bitterness is becoming less prominent in American food and drink, leading to a loss of dietary diversity and complexity. Take your time exploring orange wines, which are often produced without additives in what makers describe as a “natural” style. I have found that orange wines vary considerably in terms of flavor and quality, with some being undrinkable and others, heavenly. Some producers in Spain, California, Portugal and other locations include partial skin contact to develop texture and complexity in their wines. They ferment the wine with its skins for a short time or as a small part of a blend with conventionally made whites. White wines made with what amounts to a cameo appearance with the skins are not considered orange wines. Yet another technique for increasing mouthfeel: leaving the wine to rest as it evolves in the barrel or tank. Most wine producers rack their wines (move them from one vessel to another) several times after fermentation, leaving behind the particles at the bottom of the vessel to clarify and help stabilize the wine before bottling. Many orange wine producers subscribe to a more hands-off approach. It is their philosophy to let the wine “make itself” with as little intervention as possible, so they only rack just prior to bottling. (Non-orange wine producers can also choose to minimize racking to give the wine more personality.) Some producers ferment or age their orange wines in amphoras (clay containers) to further coax earthy, funky flavors from the grapes. While the use of clay in winemaking may seem cutting edge, it is actually a practice that goes back to about six-thousand years ago, where it originated in what is now known as the country of Georgia. Other unusual encounters with whites may include techniques that many attribute to Burgundian winemakers to enhance the wine’s mouthfeel and flavor, often using the Chardonnay grape. These include barrel fermentation and/or aging, malolactic fermentation (sour malic acid is converted to milky lactic acids), and wine aged sur lie (kept in contact with spent yeast cells). Chardonnay is often manipulated into textured wines but is not regarded as having phenolic bitterness. Incidentally, if you are wondering whether white wines contain tannins, they do, but at very low concentrations, so tannins are not addressed when tasting white wine. While Peter and I may have disagreed on the tastiness of the white plum, we do agree that Grüner Veltliner is the cat’s meow. For this reason, and others beyond his good looks, he retains his position as my key drinking partner, which is also in accordance with our marital contract. By the way, the list below is somewhat controversial among wine professionals, as not all agree upon the varieties that display phenolic bitterness. This list is more wide-ranging than many, giving us more examples to explore. Many of these varieties are ideal candidates for producing unusual textures at the very least. You might have fun going through the list to decide for yourself whether each varietal lives up to its reputation for phenolic bitterness. Bear in mind that you should try several examples of each variety because sometimes winemakers choose to mask the grape’s natural phenolic compounds during the winemaking process. Varieties with Potential Phenolic Bitterness Albana Albariño Assyrtiko Chenin Blanc (Loire) Gewürztraminer Gros Manseng Grüner Veltliner Kisi Melon de Bourgogne (Muscadet) Muscat Blanc/Moscato Pinot Blanc Pinot Grigio/Pinot Gris Riesling Robola Torrontés Traminette Trebbiano Spoletino Vermentino/Rolle Viognier This is one in a series of Grape Detective blogs featuring the attributes of wine and how your love for a specific wine grape may lead you to discover new grapes with similar characteristics. The focus of the list is grape variety and does not include blends, wine regions, or styles.  The drier your mouth feels, the more tannic the wine. The drier your mouth feels, the more tannic the wine. Tannins, to me, are the absolute magic of red wine. They contribute longevity, color, flavor, body and overall textural richness. While I adore tannins, I am simultaneously and confusingly captivated by grape varieties that are known to be low in tannins, such as Grenache, Frappato and Gamay. Just when I think, “Ah, ha! I have finally discovered my Holy Grail of wine characteristics,” plenty of opposite examples have me re-thinking my earnest declarations. This leads me to believe that there are no hard-and-fast rules about what makes a wine great. Maybe instead of seeing a bottle of wine as possessing specific attributes that you either chase or run away from, it is more open-minded and adult to view each bottle as an individual whose secrets are yet to be revealed. But I digress, so let us explore the world of tannins and why they are a subject of fascination and delight for drinkers, scientists, and industry insiders. Tannins provide structure to a wine, just as your skeleton supports your body. Without tannins, red wine would be cloyingly sweet. That is why tannins are one important element of a wine’s balance, along with acidity, fruit concentration, sweetness, alcohol, and texture. You eat and drink tannins as a matter of course because they are present in coffee, tea, dark chocolate, walnuts, cranberries and other plant-based foods and beverages. Oak can also contribute tannins to a wine, especially new oak. Producers sometimes use additives such as oak powder to increase the perception of tannins; this practice is associated with large-scale, low-end wines. Seriously, can you see yourself drinking anything that contains oak powder? Tannins are responsible for the astringent, mouth-puckering sensation of dryness you get in the mouth when drinking wine. When a red wine with firm tannins enters your mouth, it binds to the proteins in your saliva and washes much of the saliva away, leaving your mouth with a feeling of dryness and astringency, even bitterness. To determine whether a wine is high or low in tannins (or something in-between), pause to consider how dry your mouth feels during and after a drink. The dryer your mouth feels, the more tannic the wine. When you drink a delicious wine that is generous with tannins, even while the wine is still in your mouth and yet to be swallowed, why hurry? Experience wine's aromas, flavors and sensations. Much of wine tasting is thoughtfully paying attention to what is in the glass and your mouth. Drink plenty of water between sips to help your body hydrate and to produce more lubricating saliva. Pace yourself.  Tannins are present in coffee, tea, dark chocolate and other plant-based foods and beverages. Tannins are present in coffee, tea, dark chocolate and other plant-based foods and beverages. Those who are new to wine may find tannins especially challenging, even off-putting, and will find fruity or sweet wines to be much more acceptable. Eventually, however, many drinkers come to appreciate the complexity and added dimensions that tannins bring to the table. This phenomenon is similar to when you were a toddler, favoring sweets. As you grew into adulthood, your palate evolved and you began to accept and increasingly enjoy the bitterness you found in arugula, green tea, artichokes, dark chocolate, radicchio, grapefruit, beer and other food and drink, right? If you are what is known as a supertaster, experiencing foods and flavors more intensely than most people, you may find it hard to enjoy a wine generously endowed with tannins. Tannins are extracted from the grape’s skins and seeds (and sometimes the stems) when they are soaked along with the juice, before, during, and sometimes after fermentation. As red wines of high quality age, their tannins soften and interact with other elements in the wine to develop deep and complex flavors as well as a more soft and mellow mouthfeel. Aged fine wines are sometimes described as having “resolved tannins,” meaning that they have smoothed out and softened their astringency. You and I do the same thing, smooth out and soften as we age, don’t we? Wines harvested early, or in a cool vintage or location, are prone to have more aggressive tannins because the grapes have not had enough sunshine, warmth, and hang time to allow the tannins to reach full maturity. Wines harvested later, or in a warmer vintage or location, often have softer, more developed tannins. Some grape varieties have high tannins, some have low, and many have something in-between. The winemaker is tasked with understanding the tannins on offer and producing a beverage that is in balance with what nature has provided. Some grape varieties are prone to ripening unevenly on the vine, even within the same cluster, so quality producers pick only ripe grapes from the cluster, returning later for another pass at the ripe fruit. Zinfandel is an example of a grape variety that ripens unevenly. Tannins are more plentiful in grapes that have thick skins, for example, Nebbiolo. Thin-skinned grapes, such as Zinfandel, have fewer tannins. Under-ripe grapes have more tannins than ripe grapes. Nature purposefully keeps her grapes unappetizingly tannic and acidic until she is certain that the seeds are perfectly ripe and ready to be eaten and dispersed for the propagation of the species. Nature also works to woo us (along with birds and other animals) by producing luscious fruit, so she intensifies the flavor molecules in the grapes as ripening approaches. Seriously, can you see yourself drinking anything that contains oak powder? Managing tannins is an important aspect of red winemaking, and the protocol varies from vintage to vintage, winemaker to winemaker, and vineyard to vineyard. Tannins are highly complex in their makeup, behavior and development, and scientists have only begun to bring some of their many secrets to light. Without tannins, red wine would taste a lot like white wine, don’t you think? In fact, a producer can make white wine from red grapes through divorcing the grapes from their skins as quickly as possible after harvesting. However, it is impossible to make red wine from white grapes unless there is some sort of unconventional and off-putting intervention involved, such as adding food coloring. Tannins can be further described by their texture or mouthfeel. You might have heard a drinker describe tannins as “silky” or “grippy” or “sandy” or “green” or “loose-knit” or “fine-grained.” These are all descriptors that go beyond quantity to describe qualities. When you drink a red wine, think about not only the power or volume of the tannins, but also how you might describe the quality or texture of the tannins. “Firm,” “dense,” and “tightly-knit” attributes usually indicate a wine with tannins playing a key role in the wine, such as a Cabernet Sauvignon or Tannat. “Silky” or “polished” connote tannins that dance across the tongue and seemingly disappear, as with a Pinot Noir or Carménère. “Chewy” can mean tannins that coat your mouth to the point where you could practically masticate them, like a Syrah might. You might want to use terms like “harsh” or “aggressive” or “astringent” when describing a wine that is out of balance. This type of appreciation takes time and experience, so do not worry if apt descriptors do not leap from your lips when you evaluate a wine. Just be aware that these types of descriptions exist and are used by wine lovers to communicate their perceptions. This is no different than a baker comparing large-crystal sanding sugar for sprinkling atop cookies to the texture of everyday white granulated sugar.  Many drinkers appreciate the complexity and added dimensions that tannins bring to the table. Many drinkers appreciate the complexity and added dimensions that tannins bring to the table. Just yesterday I decided to open a 2018 Catena Malbec from the Paraje Altamira appellation in Mendoza, Argentina. Between us, I have come to develop a specific affinity for the texture of Malbec tannins. I view Malbec’s grainy texture as a special treat, like some people might view lobster or truffles (or sanding sugar) as a delight. This particular appetite came about by accident. I was analyzing a Grenache and returned to the kitchen to refill my glass. Absentmindedly, I grabbed the wrong bottle, poured the wine into the glass and returned to my seat by the window. (My analysis of wines involves sitting by a window to bring natural light into the mix.) The grainy texture of the tannins hit me like a slap across the face, and I knew immediately that this was not the Grenache I thought I had poured. The wine in my glass was, in fact, a 2018 Zuccardi Malbec Concreto from the same region as my Catena Malbec. The rustic graininess was in stark contrast to the fruity, low-tannin Grenache I was expecting. While confusing, it was at the same time utterly thrilling in an earthy kind of way, like laying down and rubbing your hair into the wet sand at the beach while the waves gently lap over you. (I did this once and only once; it took several washings to clean away the sand from my hair. So much for giving into my lust for experiencing the ocean’s earthy, grainy textures.) When possible, take a moment to compare and contrast a low-tannin variety with a high-tannin variety. This exercise may help you gain an appreciation for different tannin characteristics and can be especially fun to do in a blind-tasting situation. Just have a friend pour various wines for you and make notes about the tannins for each glass. Do not hold the wine in your mouth for too long, because if you do, almost any wine will seem to gain in tannic volume and your palate will tire. Then look forward to the big reveal. Of course, if your friend is also enamored with wine, you can switch places and pour for her blind tasting. To save time, you might both pour in separate rooms and then do the blind tasting together, which to me sounds like the most fun. Low Tannin Varieties Barbera Blaufränkisch/Lemberger Bonarda/Douce Noir/Charbono Bobal Carménère Chambourcin Ciligiolo Cinsault Corvina Counoise Frappato Gamay Garnacha/Grenache Liatiko Négrette Pinot Noir Primitivo/Zinfandel Schiava High Tannin Varieties Aglianico Baga Bobal/Bovale Cabernet Sauvignon Carignan/Cariñena/Mazuelo Dolcetto Freisa Fumin Gamaret Lagrein Limniona Malbec Mourvèdre/Mataro/Monastrell Nebbiolo Negroamaro Nero d’Avola Mondeuse Noire Petite Sirah Petit Verdot Pignolo Pinotage Regent Ruchè Sagrantino Sangiovese Syrah/Shiraz Tannat Tempranillo Touriga Nacional Trousseau/Bastardo This is one in a series of Grape Detective blogs featuring the attributes of wine and how your love for a specific wine grape may lead you to discover new grapes with similar characteristics. The focus of the list is grape variety and does not include blends, wine regions, or styles. |

AuthorLyne Noella Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed